7. Established HPI Institute in Atami – Global activities from a home base in Japan

1n 1970 I opened an Institute in Atami Japan named Human Performance Institute. The main reason I went to Atami was because Tokyo air was becoming polluted which aggravated my daughter Lyn’s asthma. Atami had clean air. In addition Atami is on the main ‘bullet train’ line that was convenient for institute visitors. My wealthy business friends including Dr Miyata and Mr Morita were puzzled about why I left Tokyo with many wealthy patients and university connections to go to a small town of fewer than 50,000 residents. Dr Miyata had BIG plans for me in Tokyo that extended to new buildings from the model clinic that opened in 1963. Mr Morita assumed I would soon go bankrupt after a company survey of Atami people and dental clinics there. His company paid more than $1,500,000 annually to me as a company engineering consultant. However clean air and globally oriented standards for health care were more important to me than big money, a big show or big power. Another test of this stance came shortly after my move to Atami when Dr Miyata purchased a BIG Atami building to establish a head and neck Institute with both medical and dental staff and helicopters for bringing injured patients from highways. After extended review I finally rejected the offer as the Institute director because a junkyard of cars existed along the driveway to the building. I could not accept passing by junked cars going to work every day even though the rest of the building setting was surrounded by attractive plants. Dr Miyata tried his best to buy the junkyard but the owner lived in a tent in another junkyard with no interest in accepting any offer. I sometimes wonder where I would be today if I had accepted the offer from one of the 10 wealthiest men in Japan to direct a medical-dental institute.

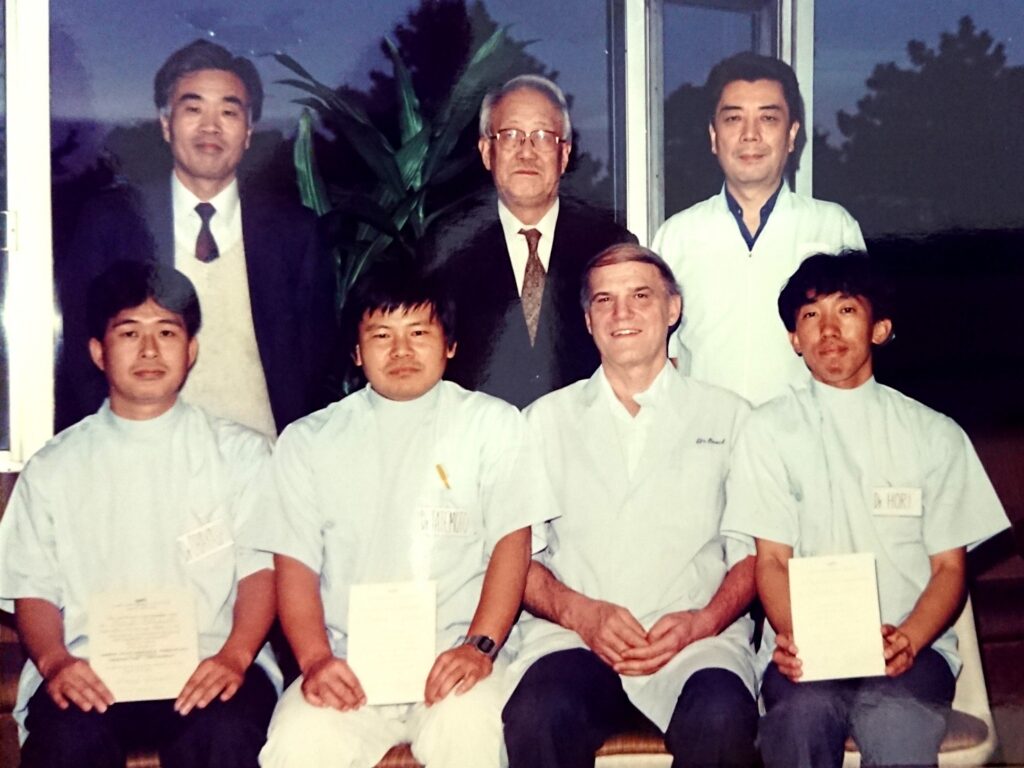

Instead I leased a floor in a large building owned by Atami city with space for research facilities, teaching facilities and a clinic that included 24 exam and treatment areas. Four exam-treatment areas plus four consultation areas were reserved for prevention specialists. Four of the exam-treatment areas were set for fixed upright patients. They were used for x-rays and other short-time procedures. HPI opened with a small staff that soon increased to more than 60 members. Most staff members worked in the Institute clinic. HPI also had visiting staff from many countries.

The main changes that differed from the Tokyo model clinic were-

- Deletion of most walls. Walls are vision and sound barriers to everyday communication)

- Deletion of dental chairs that tilt patient bodies. (the clinic was similar to physician clinics where patients self-position to flat surfaces for exams and treatment and self-position to upright seats for consultation).

- Deletion of positioning devices for trays, instrument holders and operating lights.

These deletions enhanced the value of the HPI courses but it also deleted the need for a high variety of chair-based equipment and related instruments which the dental equipment industry depend on for their living. HPI caught attention –and the rejection of the dental trade – when a clinic chain developed from copies of the HPI Clinic made by HPI alumni. By the late 70s the dental trade opposition was becoming organized against HPI more from frustration than from intention. A clinic maker had two basic choices –believe HPI or the thousands of equipment and instrument salesmen. This stand-off continues today which can have much effect on the quality and economy of dental care. The stand-off on conditions for dental procedure has evolved from a Beach-HPI stance centered in Japan and an ISO Work Group 3 centered in a German company to an effort to achieve consensus between GEPEC (Global Engineering Promotion and Education Collaborative) centered in the US and ESDE (Europe Society for Dental Ergonomics)

Health Oriented Index:

A few years later I changed the HPI Institute records to Health-oriented patient-clinic records in numeric orders. The HPI Institute procedure manuals were converted to xyz, numeric orders and one-minute time points for information and procedure credits.

Encounter with Don –

An instructor of surgery at Harvard and resident surgeon at MIT saw our connection between medicine and dentistry. His name is Don Butterfield. On a visit to Japan he needed removal of a wisdom tooth well buried in bone. He watched me remove it while holding a mirror in the Tokyo model clinic. The next day he took many photos of the clinic. He later returned annually after I moved to Atami. One day he asked me what I would first do If I were invited to the abdominal surgery department at Harvard to teach surgery residents. This request ended his teaching career at Harvard. I told him I would blindfold the residents and ask them to perform the most routine procedure in open space to see if I had any useful information for them. He said appendectomies were most routine so we went to an empty hotel lobby on the next floor where he ‘performed an appendectomy’. I asked him the average time he needed for the procedure. He said “I am a fast operator, my average time is 18 minutes” so I recorded the time with a stop watch. He did it in 18 minutes so he probably had clear mental imagery. Two notes upset him. I noticed he made quick arm jerks sometimes and even said ‘damn it’ Also when he shifted to the left he pulled the elbow close to his body. His jerks came from replacing slipping retractors held by nurses; the tight elbow was caused by an ether curtain. When Don asked his professor why they were using easy-slip castings for retractors and why do they have ether curtains when ether is no longer used, the answer was Harvard has good reasons for everything. The answer did not satisfy Don so he resigned his teaching job. On his next trip to Japan Don wanted drawings of The HPI clinic designed for medical practice. The openness appealed to him and he had convinced some medics to accept it. Visual and sound barriers were increased somewhat but not excessively for medical patients. Sliding gates opened the clinic in the morning to the reception areas and closed it at night –no doors there. After he prepared the clinic drawings the Boston Medical group refused to accept them based on reasons difficult for us to understand. However he was getting a taste of problems HPI faced including the dental association refusal to accept HPI dentists as members. I never cared much about that since medical and dental associations are not really a benefit to patients or the public in general.

The dental trade consists of many competitive companies with thousands of salesmen. Some makers made an honest effort to find a way to market the system called ‘Performance Logic’ at that time but they always returned to the dilemma that faced the Ritter company. The dental industry depends on sales and service chains of local dealers that offer choices of products while HPI addressed total clinics and had direct access to both engineers and end users including patients.

Two top executives of one of the largest US dealer chains (Patterson) came to HPI for 10 days to honestly capture our concept. On the 1st day I told them that 3 days should be enough for executives to decide whether or not they want the human centered system for a lifetime as 1) a patient 2) clinic owner or administrator 3) a dentist 4) a clinic coworker. At the end of 3 days they were fully convinced. We than had one week to discuss how they would market the system with the existing orientation of their employees and sales branches. As I recall our discussions lasted a few extra days. We finally gave up on how dealers could successfully market the HPI system based on product choices in dental shows and pamphlets. The HPI system was based on the feel of tissue stretch and body contact while the market was based on eye catches of products that divert attention from what is really important –body centered information on body use.

Today we have shortened the name of the system to ‘pd’ which abbreviates proprioceptive derivation/proprioceptively derived’. Pd is based in the sense of tissue stretch that confirms optimum body segment positions, their paths of motion and everything that affects the body positions and movement in health care settings. Full application of pd decimates the variety of products so we do not expect further support from dental equipment and instrument dealers. It gradually became clear that only the end users – patients and clinic personnel- plus WHO and health ministries benefited from these standards.

Patient care records in digits –

By the late 1970s HPI became deeply involved in numeric records of patient care and numeric procedure manuals before the advent of electronic records because some administrators of dental schools began to have interest in HPI. We were asked how we could ‘prove’ that HPI standards had short term and long term benefit on patient care. I took a good look at the entries in HPI’s thousands of patient charts and decided that all the Japanese, English and German words and abbreviations that were accepted by the dental association for record entries could demonstrate nothing in terms of quality of dental care. For example it was nearly impossible to scan the records for re-treatment rates. Also we found that procedure manuals based in xyz-time and numeric orders were far superior to manuals extensively worded in English or Japanese when compared with consistency in accuracy of outcomes and learning time along with perception of detail in procedure steps.We also found that dental schools and dental associations are not organized to accept the benefits that computerized patient records and procedure manuals can offer to patients and students.